As we moved into a fresh, shiny New Year last month, many of us set goals and plan for where we hope to be by the end of the year. We anticipate with optimism the benefits that will come to us from choosing to make changes in our life.

By Veronica Harvey

Senior Consultant

Reprinted with permission from her blog

As we moved into a fresh, shiny New Year last month, many of us set goals and plan for where we hope to be by the end of the year. We anticipate with optimism the benefits that will come to us from choosing to make changes in our life.

What we may give less thought to, however, are those changes that will inevitably be thrust upon us, changes we didn’t plan on, yet must respond to given the VUCA world we live in (Volatile. Unpredictable. Complex. Ambiguous.). For those of you unfamiliar with VUCA, the concept was first introduced by the U.S. military as the Cold War was ending and a multilateral, global landscape was emerging. But more simply, as Scott Berinato noted in Harvard Business Review, it has become another way to say, “Hey … it’s crazy out there!”

While experts differ on the predictability of change, most of us can agree that we will likely be grappling with change on a regular and increasingly accelerated pace.

On a daily, even hourly basis we are bombarded with news on technological change, climate change, social change and most certainly political change. What’s more, we are now forced to discern what accurate information is and what is fake news or propaganda.

When I was growing up in the 1960s, the idea of voices and data traveling through time and space without any wires or physical connections seemed like impossible science fiction. Yet today, few of us could function without our smartphones. And in all likelihood, we’ll soon have technology at our disposal that surpasses what we can even imagine today. If we cannot keep up with change as leaders, how can we expect our employees to do so?

Given the constant of change, a resolution to become more agile at learning and adapting seems less of a luxury and more of an essential.

Throughout history, those men and women who learned new and better ways to do things were more likely to survive, and thrive. Being able to learn a better way, a new approach, a different skill allowed some individuals to better adapt. Learning is ultimately the evolutionary advantage that we can control. What makes learning especially important today is the pace and complexity of change. The world we live in creates a pressing demand for both leaders and organizations that are highly agile and adaptable.

In order to remain agile, leaders must have the capacity to le

arn at or above the rate of change.

I have had had the privilege of observing, assessing, training and coaching literally hundreds of professionals and leaders. In addition, as a result of both my work and my education in the field of psychology, I have been exposed to numerous thought leaders and researchers in the field of leadership, learning, career development, positive psychology and coaching.

As a result, I am convinced that the most important capability any of us can develop is knowing how to learn.

The idea of “learning to learn” may seem strange. Typically, learning is viewed as a means to an end. We go to elementary school to learn to read, we take a class to gain new knowledge, and we go to university to learn a profession. We learn for purposes of doing something else. But it is relatively rare to find someone who has been taught not only WHAT to learn, but HOW to learn.

Knowing how to learn may be the single most empowering capability you can develop.

Part of what makes us human is the desire and capacity to continually grow and become better. No matter our age or career or life stage, there are always opportunities to expand. For some of us, this may be in our ability to lead others and be effective at work. For others, it may mean learning new mindsets and approaches for interacting with our friends and loved ones. And as we age, it may mean learning to do things in different ways to accommodate our physical limitations. When we stop learning and growing, we start contracting and dying.

While this is the cycle of life, we can take some control, by learning how to learn.

Because learning agility is now viewed by many organizations as a critical aspect of leadership potential there has been considerable focus in recent years on selecting leaders who possess learning agility “traits.” This school of thought emphasizes predicting characteristics that are relatively fixed using formal assessment methods such as tests and assessment centers.

These “fixed” characteristics include things such as cognitive ability along with personality characteristics such as openness to experience, intellectual curiosity and need for achievement. No doubt, these characteristics are important, worthy of assessing and may make it easier for some to learn and adapt.

However, many aspects of learning agility can be learned by all of us.

For example active reflection, feedback seeking, and goal setting have repeatedly been found to facilitate learning the primary focus of my posts will be on behaviors that can be learned and that will allow you to take charge of your life regardless of the traits you were born with or the circumstances that you find yourself in. Even for those blessed with natural learning “instincts,” developing learning skills can dramatically accelerate the learning journey.

Learning is a process of becoming, of choosing who we will be in the future... This learning can happen through trial and error (often at the price of pain and suffering) or by being more strategic in how we learn. At times, learning involves “doing” and at other times “being” will be more important. Some activities involve working independently and at times learning is best done with the wisdom, help and involvement of others.

For many years we have relied extensively on the 70-20-10 formula for learning.

This model, dating to the early 1980s is credited to Morgan McCall, Michael Lombardo, Robert Eichinger and the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL). The premise of the model (which was the focus of my graduate dissertation) is that leaders learn best through means other than formal training and that development should be about 70 percent from on-the-job experiences, 20 percent from feedback and learning from others and 10 percent from courses and reading. The model has certainly served us well in broadening the focus on how leaders learn and in communicating the importance of learning outside of a classroom.

But, the pace of learning needed in today’s world requires more sophisticated approaches yet at the same time, methods that are exceedingly practical.

It is time to start thinking of learning as a three-dimensional process that can happen every day.

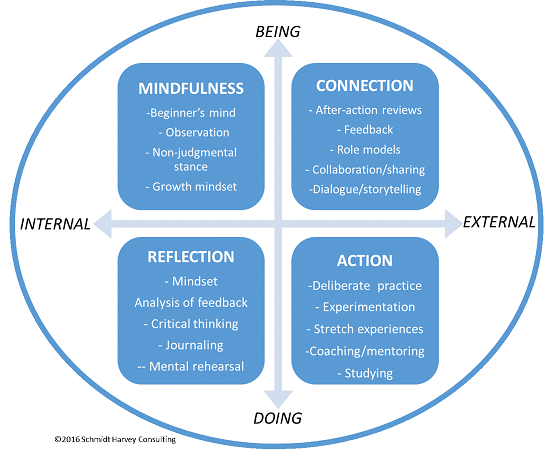

The first dimension of learning differentiates between learning that is done independently (internal) versus learning that requires the involvement of others (external). The second dimension focuses on active learning (doing) or focused attention (being).

These two dimensions allow learning approaches to be grouped into four quadrants of 1) Mindfulness (internal/being), 2) Reflection (internal/doing), 3) Connection (external/being) and 4) Action (external/doing). Within these four categories, multiple techniques are possible as noted in the diagram below:

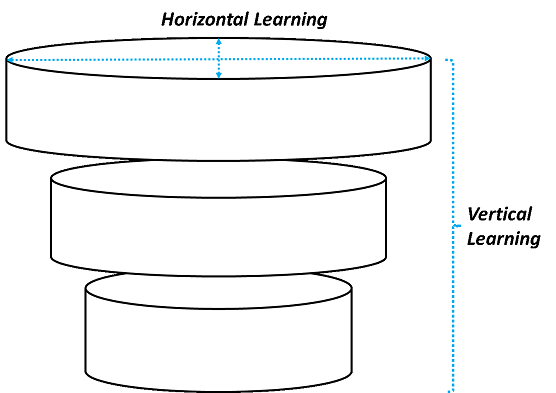

The third dimension of learning differentiates between horizontal and vertical learning and is a more difficult to wrap one’s head around. Horizontal learning involves expansion of knowledge, skills and abilities. Most of the learning we are accustomed to tends to be horizontal.

Vertical learning is about changing the way we make sense of their world, expanding our capacity for meaning-making and transforming or reframing the ways we view reality. Researchers also describe it as “metacognition”, or the ability to reflect on your own thinking processes. If you have ever experienced a transformational learning experience, you’ll often find it was something that changed your entire way of looking at the world. An analogy used is that horizontal development is about adding space to your computer’s hard drive, while vertical learning is about increasing the speed and power of your processor.

To use another metaphor, horizontal learning has been described as pouring water into the same old container (the mind). The mind fills up, but the container doesn’t change. Vertical development is about changing the container. While vertical learning may seem like a futuristic concept, it’s actually not new. Even Jesus in the Bible talks about not using old wineskins for new wine.

In future posts, I will share more details on techniques you and others in your organization can use to accelerate learning “up, down and all around”. But, the first question you will need to answer is whether you will benefit from learning how you can learn better.

A simple test for whether you have a need to LEARN can be answered by two simple questions: 1) Are you as successful as you would like to be? 2) Are you confident you can adapt to changes you are faced with?

Consider this question broadly, from the standpoint of your personal life, professional life, health and emotional well–being. I think there are very few of us who can give a resounding “yes” to both of these questions. (And those that can are either masters of learning or may need to ask if they are deluding themselves!).

It is said that you cannot solve today’s problems with yesterday’s mind. We must evolve just to stay credible and relevant. I hope that you will join me on the quest to become more learning agile, to empower yourself and others to deal with change and thrive in both 2017 and the years ahead. I look forward to the privilege of helping you “learn to learn” and in ways large and small, transform your life and business.

Let’s get GROWING!

©2017 Veronica Schmidt Harvey